On Jan. 26, a coalition of civil and disability rights organizations filed a lawsuit petitioning the California Supreme Court to strike down Senate Bill 1338, also known as the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Court Program, arguing that the program would violate due process, equal protection, and autonomy rights.

Signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom in Sept. 2022, the bill attempts to address the mental health crisis and homelessness by using the court system to mandate a 12-month personalized care plan for individuals with psychotic disorders, rather than have them on the streets or

in jail cells. In the first phase, seven counties, including Orange County, were selected to implement the experimental framework by Oct. 1, 2023, while the rest of the state would follow suit in the second phase.

Although perhaps well-meaning, the CARE Act is thoughtlessly ambitious — not only does it fail to take into account the sheer amount of resources necessary to implement the changes, but also threatens the autonomy of vulnerable populations.

In an attempt to tackle both homelessness and the management of psychotic disorders, CARE courts overlook the greatest issue surrounding

homelessness in California: there is insufficient housing to meet demand and deep-rooted structural factors, such as single-family zoning policies and local opposition to housing, prevent the construction of homes. California is also a state with high job growth, which entices people to live there and drives housing prices up.

Civil rights and disability groups’ major concern surrounding the CARE courts is that they infringe upon the autonomy of disabled individuals. While courts cannot force individuals against their will, there can be steep consequences for failing to adhere to their treatment plans, including conservatorship — the legal appointment of a guardian to manage the financial affairs or daily life

of another person if they are deemed incapable of doing so themselves. Despite the high requirements for conservatorship, the CARE courts create a direct route for individuals to be stripped of their rights.

Many details will have to go into implementing CARE Court, such as training judges to handle cases pertaining to mental health in a new civic court branch. Additionally, the housing plan remains vague — counties are expected to provide housing options on their own.

Instead, California needs a solution that prioritizes finding permanent

housing for individuals. A housing-first policy recognizes that homeless individuals must first find a stable and safe place to live before seeking

treatment for other issues. Such an approach would result in higher rates of housing retention and lower hospitalization rates for psychiatric disabilities.

Despite well-meaning intentions, the program contains glaring issues with its controversial court-mandated approach to mental disorders and its oversimplified plan. Disabled individuals deserve care that provides them with stability without treading on their rights.

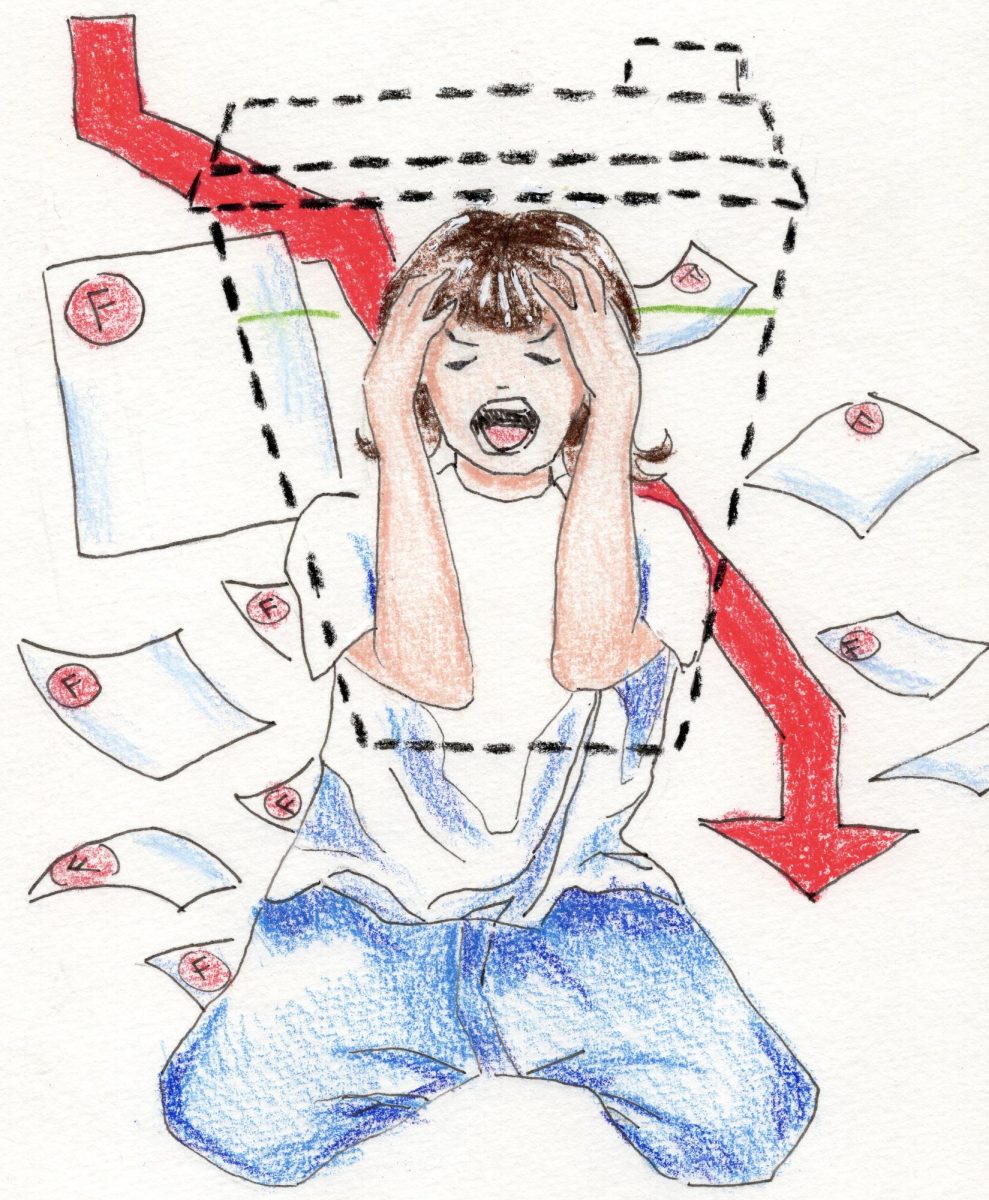

![Escaping the College [Admissions] Rat Race](https://oagamut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/mayoped-750x900.jpg)