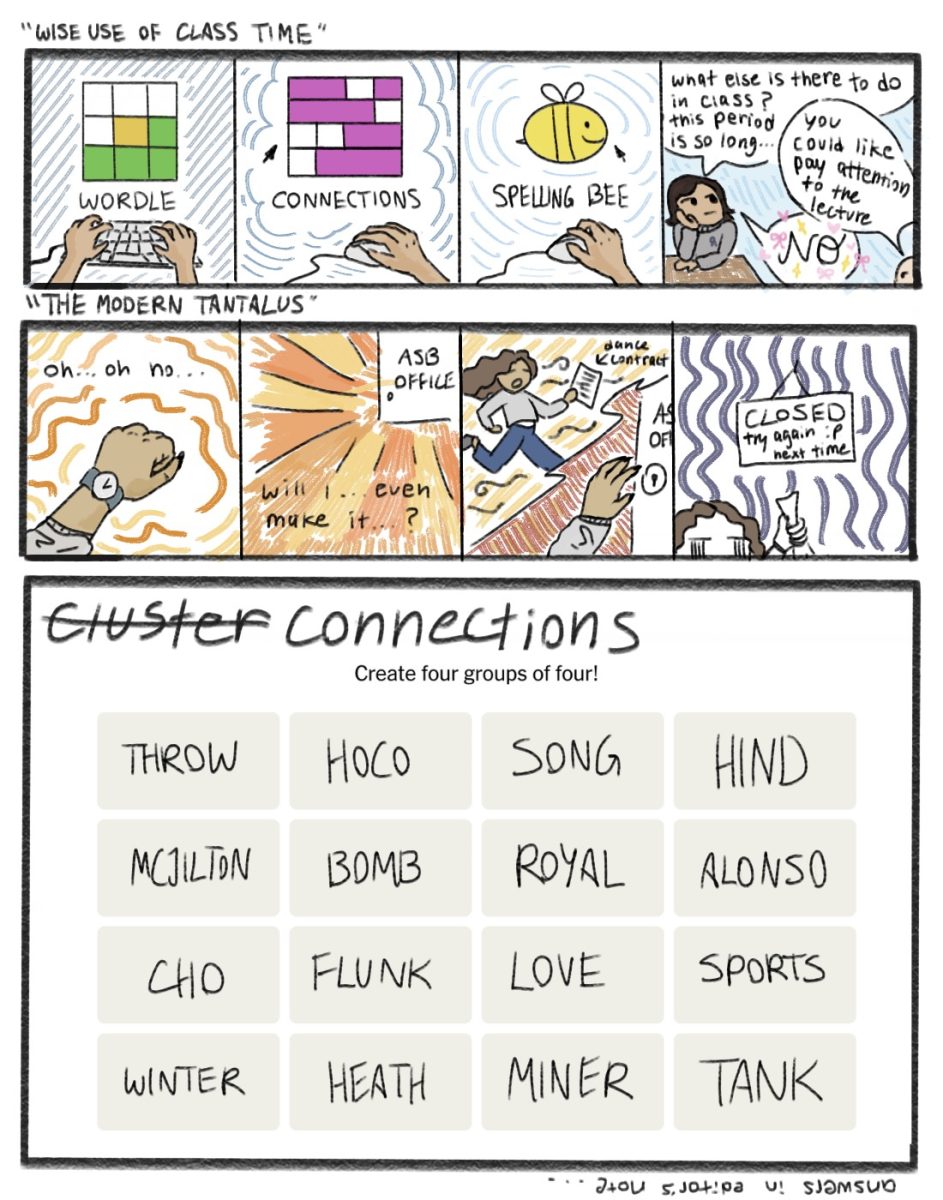

In a success-focused world, the constant drive to optimize productivity has plagued Oxford’s student culture.

Social pressures push students to squeeze every drop of spare time into something “worthwhile,” often hidden in habits like working during lunch and staying up late to finish “just one more assignment.” As more students become entangled in this demanding loop, it is imperative to dismantle toxic productivity by recognizing the unhealthy ideal and reframing what constitutes “being productive”.

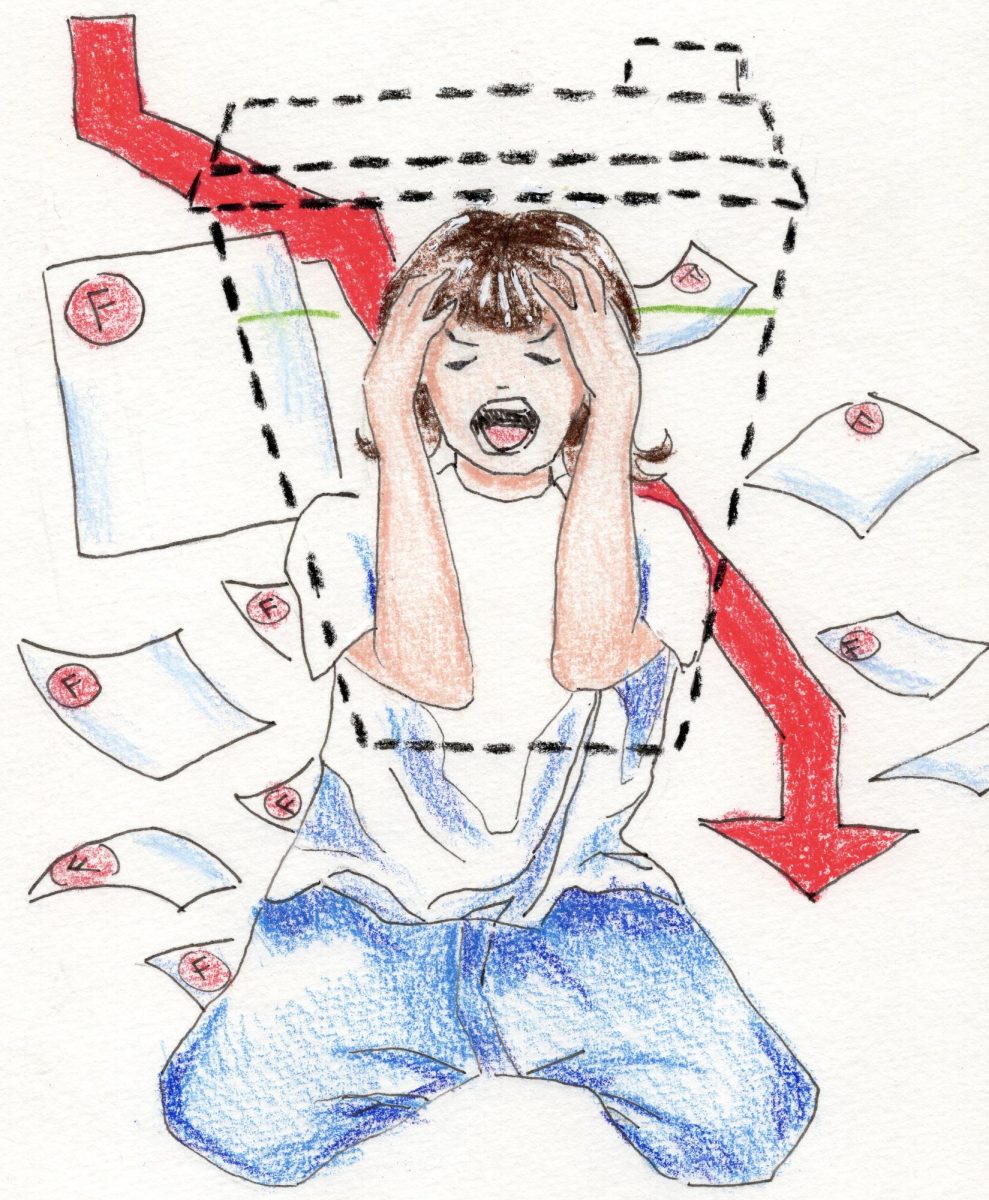

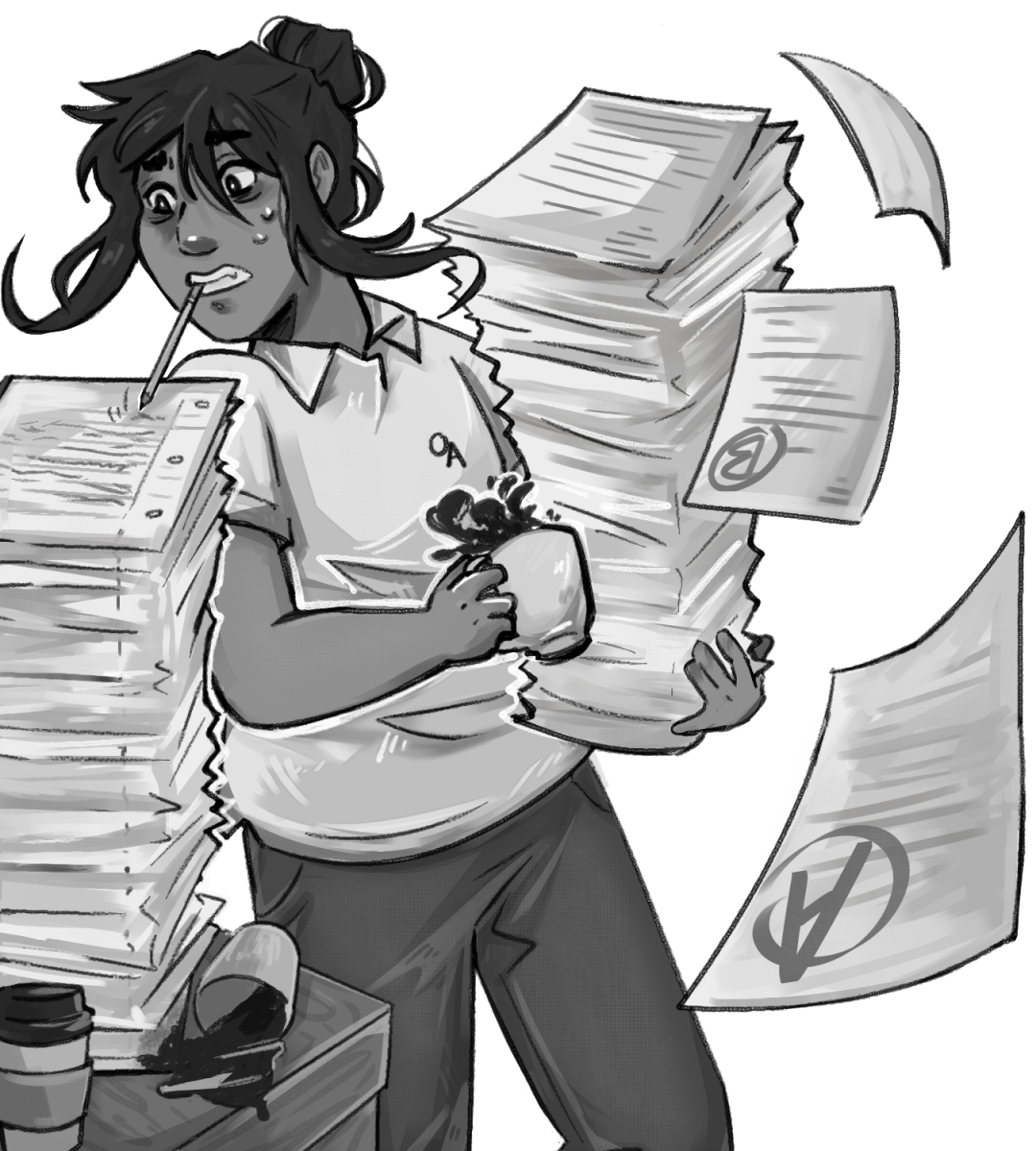

When students chase constant productivity to keep up with their peers and school demands, they inadvertently sacrifice the boundaries of their personal lives. Relationships with loved ones are strained. Hobbies become business endeavors or resume fillers. Caffeinated drinks replace much-needed sleep. Ultimately, in this monotonous cycle, when one’s health takes a backseat to academic achievement, productivity turns into burnout.

According to a 2014 research paper by John Pencavel, an economics professor at Stanford University, working over 50 hours a week significantly decreases productivity per hour, with a steep drop after 55 hours, rendering additional hours useless.

“Students who spent more hours on homework…were more stressed about their school work and tended to report more physical symptoms due to stress, fewer hours of sleep on school nights, less ability to get enough sleep, and to make time for friends and family” according to a 2013 study co-written by Denise Pope, a lecturer at Stanford.

Ironically, seeking to optimize productivity can result in a lack of motivation and lowered performance, or in other words, what society deems “unproductivity.”

When one’s health takes a backseat to academic achievement, productivity turns into burnout.

Equating success to productivity makes students feel guilty when unable to complete their never-ending to-do lists or if they dare to take a break. This unhealthy mentality fosters an environment where being “lazy” is a failure, pressuring students to over-commit. Intertwining self-worth with productivity can result in self-condemnation, making it even more difficult for students to prioritize self-care and well-being.

However, productivity and working hard are often key to academic success. Diligent study habits yield good grades, and participating in expansive extracurriculars results in a good resume — two aspects that attract prestigious universities and establish a reliable path toward a successful career. Thus, a student who dedicates their entire life to working and studying represents the pinnacle of success everyone is encouraged to achieve.

This dangerous mindset culminates in a culture where students are forced to compete to see who can sacrifice the most out of their lives to stand out. In an environment of internalized competitiveness masqueraded as simply “working hard and maximizing productivity,” healthy boundaries and balances are abandoned.

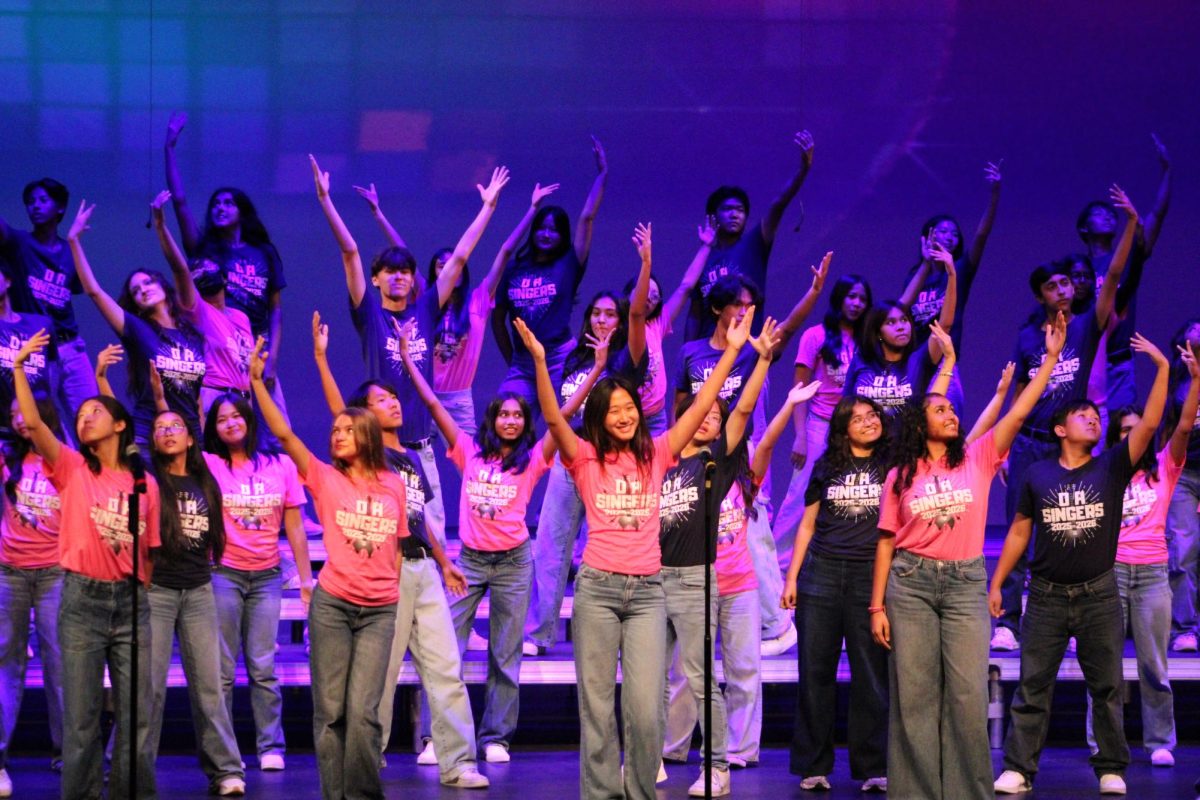

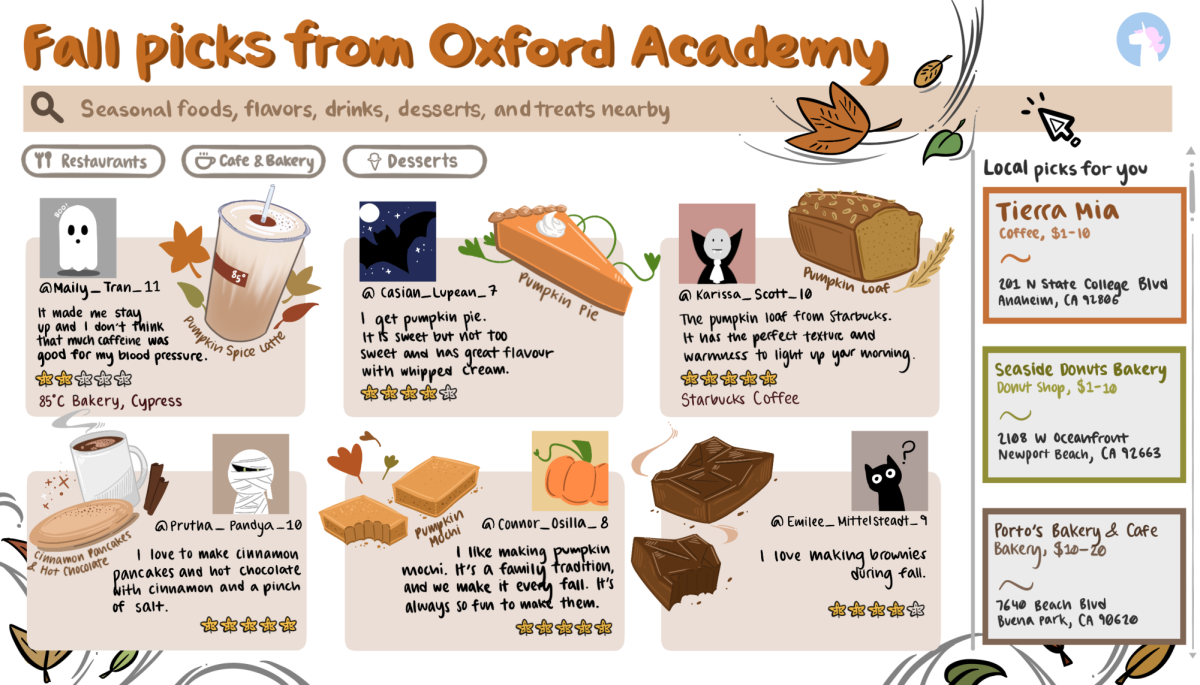

To escape the relentless hustle culture, productivity must be redefined. It shouldn’t be exclusively limited to academic or professional gains but rather encompass self-care, personal growth, and fulfillment in life. Often, it is low-stakes activities — such as baking, knitting, and gardening — that make students the happiest. Everyone deserves rest and leisure, not as a means to facilitate more work, but just to enjoy.

Students must let go of unhealthy expectations of success, recognizing that setting boundaries between personal and academic life is not weak. By practicing self-compassion, they can learn to acknowledge that it is okay to have setbacks, progress at their own pace, and be “unproductive.” Life offers so much more after high school, so devoting one’s whole existence to unattainable perfection is futile. Students should aim to create a school-life balance and focus on personal progress, taking the time to enjoy life in the moment.

Students can also take external steps like seeking help from teachers or peers, whether requesting an extension or just a check-in. They can prioritize their well-being by establishing boundaries, like when or where they work, scheduling breaks for rest and social connection, and learning to say no to avoid over-committing.

Toxic productivity can’t be solved overnight, but being mindful of its symptoms and consequences is a vital first step. As Thanksgiving break approaches, students shouldn’t feel guilty about not being productive. Instead, they should enjoy hobbies that bring them joy because creating happiness is in fact productive.