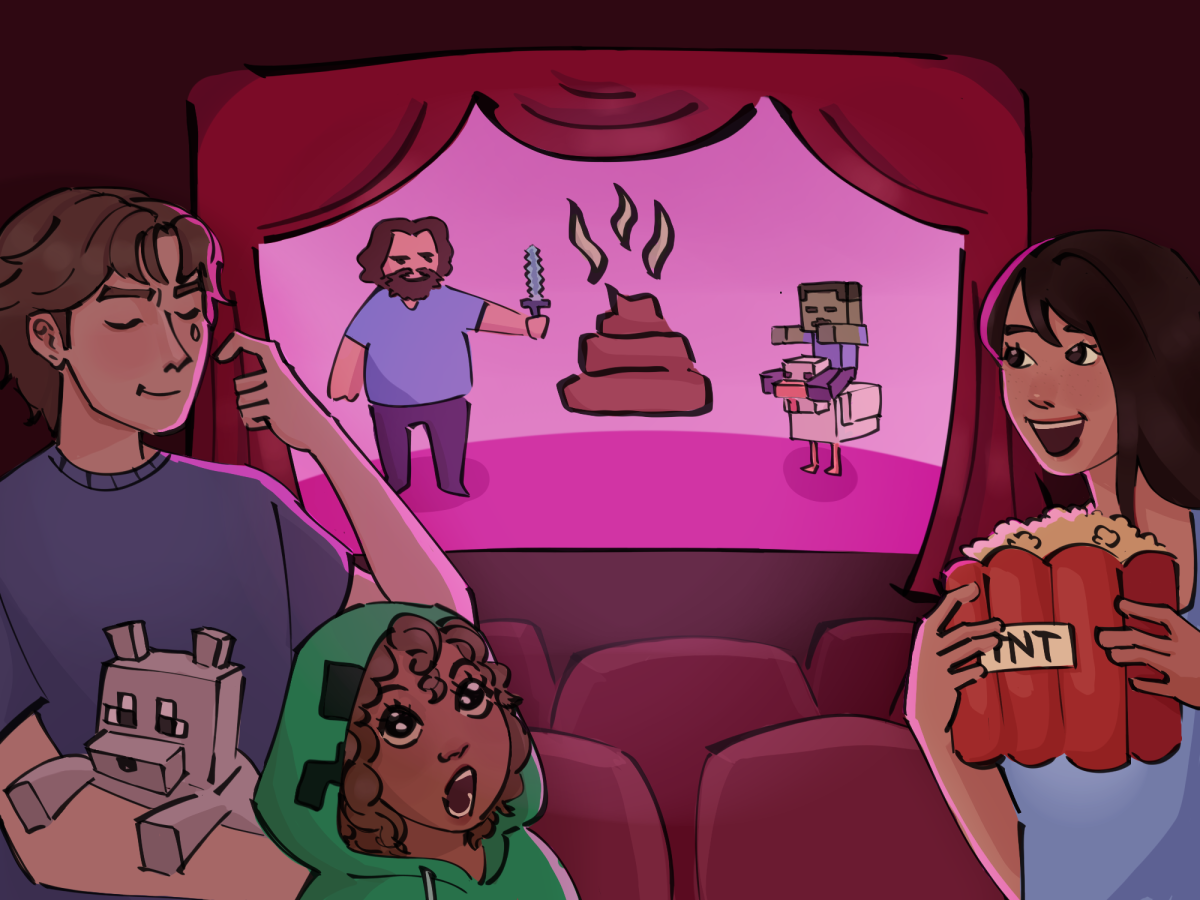

Amongst past idol survival shows like “Produce 48” and “I-land,” “Boys Planet” has recently emerged as another production from the popular Korean TV channel Mnet. The competitive reality show, airing from early February to late April, has set itself apart with an international and interactive twist. Featuring a cast of 98 trainees, split between the “Korean Group” and the “Global Group,” and live audience voting to determine who makes it to the next round, “Boys Planet” aims to create the next global K-pop boy group with the final nine contestants.

Although created as an opportunity for Mnet to salvage their reputation from previous vote-rigging scandals, the audience-oriented voting system in “Boys Planet” faces bold-faced intervention from the production team. With this ultimately destroying Mnet’s intent of making an unbiased, fan-chosen group, the K-pop reality TV industry needs to take more decisive actions.

As many reality shows do, conversations between the contestants are intentionally edited to create a dramatic narrative. However, “Boys Planet” has taken a step further by deliberately cutting out scenes with international trainees and disproportionately shining the spotlight on South Korea’s favorites. When international contestants do appear on screen, they are usually painted in a negative light, such as when one is acting careless during training sessions or when an argument has struck out between trainees.

Mnet set the G-group up for failure from the very beginning, where many contestants’ debut performances weren’t shown in the first and second episodes. The absence of screen time resulted in the audience’s unfamiliarity with G-group trainees, putting them at the bottom of the rankings and contradicting the merits of the audience-led voting system.

Additionally, after a near landslide victory of K-group winning six out of the seven matches against G-group in the first group battle mission, despite G-group having many more stable and dynamic stages, nationalism is evident in the judges’ evaluation of the performances. Alongside the judges’ heavy criticism of G-group’s Korean pronunciation while singing, Mnet’s deliberate choice to not hire translators between trainees speaks volumes about the K-pop reality TV industry’s view towards foreigners: not worthy of being taken seriously unless they adopt a Korean image.

In consecutive episodes, producers have exploited the language barrier between the K-group and G-group trainees, warping mild miscommunication into antagonistic interactions. What may have started as a means for comedy and drama has significantly affected the trainees’ reputations and their chances of survival on the show — especially when some South Korean fans began using these scenes to justify their xenophobic views towards the G-group candidates. For instance, Chinese trainee Krystian Wang received an influx of online hate after a dramatically edited and out-of-context scene portrayed him as disrespectful and rude to his team members.

As part of the new generation of Korean survival shows, “Boys Planet” has the potential to be the stepping stone for a more diverse K-pop industry. However, this dream may never become a reality if issues of nationalism, xenophobia, and bias in show production remain unaddressed by broadcasting channels and ignored by millions of viewers. The future of K-pop lies not in the popularity of these shows, but in their efforts for fairer and more mindful media production.